Performance Practice for Indeterminate Scores

Or, how to "get good" when there's no precedent for "good"

I’ve had the recent good fortune of being awarded a small research grant for the next few months to tackle one piece of my research into the postwar avant-garde, thanks to the Staatliches Institut für Musikforschung, Preußischer Kulturbesitz (“State Institute for Musical Research, the Prussian Cultural Holdings,” hereafter “SIM”), the largest non-university research institute dedicated exclusively to music in Germany.

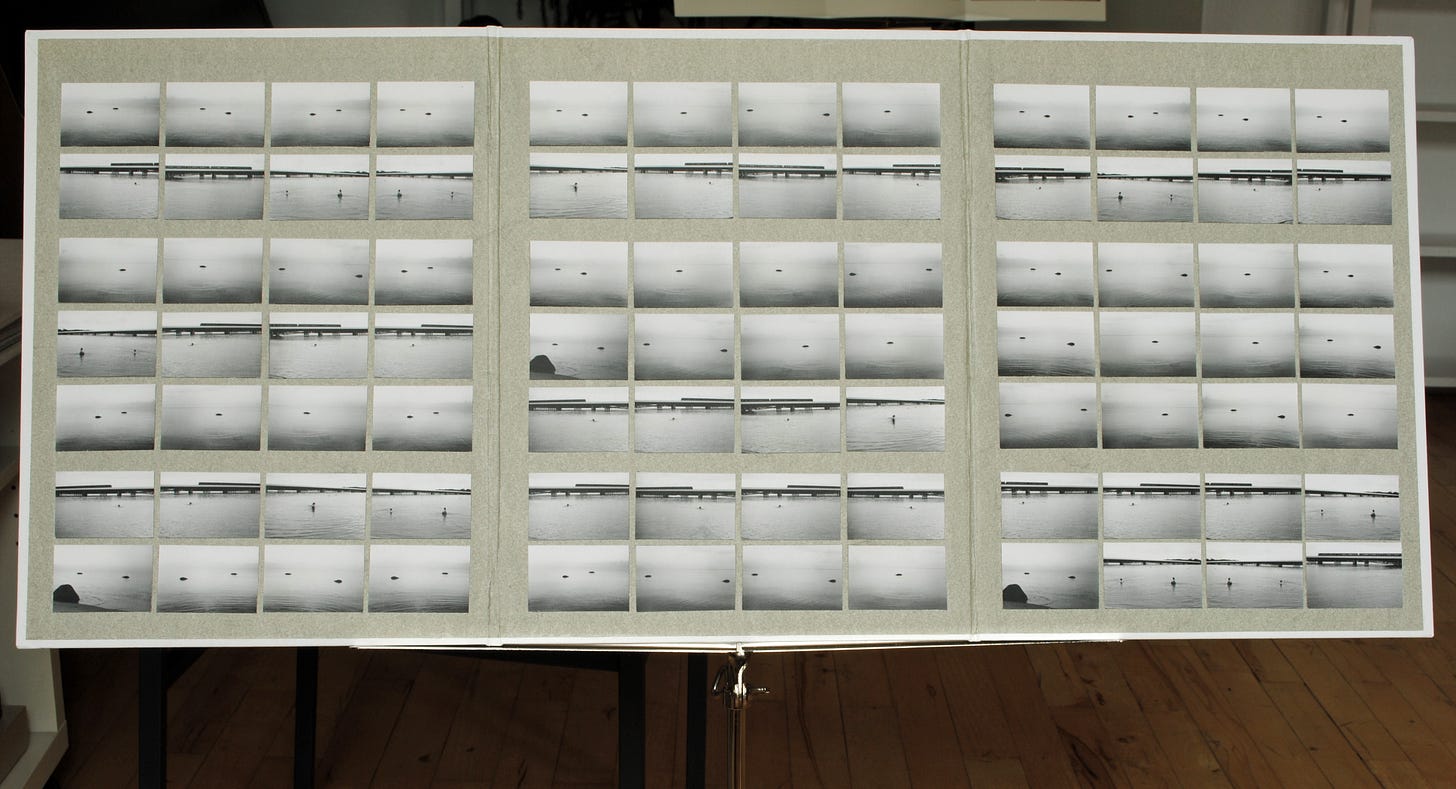

I’m extremely excited about this not least because it’s a paying job in my chosen field, but also because it will enable me to work on a specific question I’ve had about the field of music that I’ve been talking about here. I’ve written previously about the challenges of writing performance instructions for graphic scores, but there’s a second issue that’s also almost entirely unaddressed in musicological circles: what is the nature of “performance” in this context, when performing music that is completely indeterminate in its sounding result?

I think the most succinct description of the problem is a question I frequently face when working with performers on one of my own scores: “how do I know that the performance is good?” It seems like the answer would be self-evident, but it’s not so simple when dealing with scores that sound different every time you perform them. The normal way you improve a performance, the measure by which you judge a performance to be good, is to compare what you did the last time with some target version, and then iterate. But this comparison means listening to the sounding result, and assumes that the next time you perform the piece it’s going to be essentially the same sequence of sounds, this time closer to some imagined, ideal version. If, instead, the performance is non-reproducible—that is, if it’s different every time—there’s no ideal version, no target, and thus no possibility for comparison and iteration. So how, then, do you know if the performance is good?

Historical Performance Practice

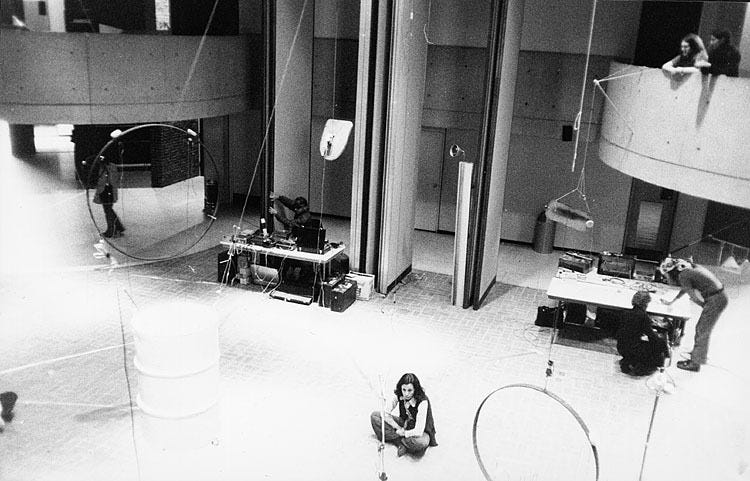

This question is also relevant for the historical portion of my research: how did composers and performers organize and present performances of their works, when there were no precedents to guide them? We know of some famous examples, like the notably scandalous (and arguably failed) performance of John Cage’s Atlas Eclipticalis, covered in some detail by Benjamin Piekut. However, there were many other instances where otherwise classically trained musicians approached difficult indeterminate scores and produced memorable and groundbreaking performances.

A lot of that work was, of course, couched in terms like “experimental,” I suspect partly to shield it from questions about quality or attainment. And just as many other composers described what their performers were doing using terms like “improvisation,” which I also suspect was partly a shield, but also partly an effort to explain what the musicians were doing in terms where their technical achievements were comprehensible (improvisation, even by the mid-20th century, was a known art-form with familiar measures of attainment and quality).

But I don’t believe that performing a graphic score is a free improvisation, in the sense that it’s driven by internal impulses from the performers themselves (I realize other composers view this differently). For me, while performing a score like this uses the tools of improvisation, the driving impulses behind the performance do not (entirely) originate with the performer. The score must necessarily play a role, or else there’d be no need for it. So how, then, do you know the performance is good?

Performance Research in Indeterminacy

This is what my research project at SIM is going to attempt, because there is evidently something of a gap in our understanding both of the historical practice and its contemporary form. There’s quite a lot of research in performance studies, covering what and how performers think while performing, how they and other involved parties think about the act of performance after the fact, how our culture perceives performance, what the æsthetic valuations of various responsibilities are and how they change, etc. etc. But as far as I can find, precious little (if any) of that research has addressed how those factors might change when dealing specifically with situations where performers are playing from a score with indeterminate outcome.

The language we use to describe performance has been in flux throughout the twentieth century as well: in German, for example, there are nontrivial differences in referring to a performer as “Interpret(in)” (“Interpreter”), “Künstler(in)” (“Artist”), “Performer(in)” (“Performer”) or some other term (the “-in” suffix is the feminine form). While much of the difference seems to derive from how much creative input the various parties are seen to contribute to the final result, the language for the various roles seems likewise to be inadequate to describing what’s happening.

To address some of these questions, I’m going to be spending my summer conducting interviews with some of the people who were on the front lines, as it were, in those first waves of experimentation in Germany: those artists who were involved in introducing Cage, Logothetis, Haubenstock-Ramati, or other composers to the audiences of the 60s and 70s. How involved were the composers? Did the ensembles have other mentors? How did the press regard the undertaking? How did the public receive it? How were rehearsals organized? Were there rehearsals? Many of those involved were students at the time; how did their professors react? Was there institutional support? Did the language they used to describe what they were doing, how they saw themselves, how they understood their own work, change in the encounter with indeterminacy? And lastly, how have the answers to any of those questions changed in the ensuing fifty or sixty years?

I’m not sure how much I can accomplish within the relatively short grant period—three months is a very short time to conduct research and write up the results—but it will at least be something of a start. I have bigger questions I want to investigate that will follow on to these questions, so it’s also a necessary step before I can get into the deeper research. And of course, in the meantime I also want to be addressing some of these questions in my own creative work, as I take up composing again and start working with ensembles on scores of my own. I confess that I’ve faced difficulties in the past in these situations—performers want to have some metric to judge their performance, and if the composer refuses to give any it can lead to feeling like they’ve been cast to the winds—so it’s something I’d like to investigate out of my own self-interest, as well.

One of the things that I think hinders the musical arts being taken seriously is that a lot of us seem to have given up on questions of attainment, excellence, quality, or judgement in our field since the sixties. There have been efforts to get public institutions to treat the arts with the same seriousness accorded the sciences—witness, for example, the proliferation of “centers of excellence” or “artistic research” at music schools in the US and Europe—but I think one of the main problems is simply that we’ve never developed a way to argue compellingly that an artist’s achievement in the arts of the postwar avant-garde can be rigorously measured. To a certain extent, we can’t even say what we’re measuring, or know what language to use when doing so.

I certainly don’t want to return to the arts of older periods, prior to the twentieth century, when a general consensus of taste could reliably be applied to judge an artist’s accomplishments. But if we’re going to go forward, it’s also going to have to be based on something other than merely subjective opinion, or personal preferences. As a first step, I hope this research project can get some documentation of the originators of these new arts, to get first-hand accounts of what it was like, in those heroic times, when the artists of the postwar avant-garde created the world anew.