I generally find it helpful, when dealing with concepts that are novel or unorthodox, to clarify where exactly the boundary lies and define the entities that exist on either side of it. The scores I’m interested in are a particular subclass of “graphic” scores, and I don’t think it’s enough for me simply to say they don’t use “conventional” notation. After all, conventions are contingent and mutable, and what might have been considered a “graphic” in the 50s might just become the norm in the present.

As a good example of what I mean, consider this snippet from one of Helmut Lachenmann’s most well-known scores from his early period, a piece for solo cello called “Pression”1:

At first glance, this looks extremely “graphic” and would likely be featured in any mid-century compilation of innovative musical scores, but on closer examination it is still very clearly following the conventions of music notation (albeit using continuous lines rather than discrete noteheads, and using the diagram of the cello’s strings to indicate playing position rather than a five-line staff to indicate pitch).

Even without being able to read music notation, if I told you the horizontal axis was time, and the vertical corresponded to position along the strings, leaving aside all the other markings I think even an untrained listener could more or less follow along.

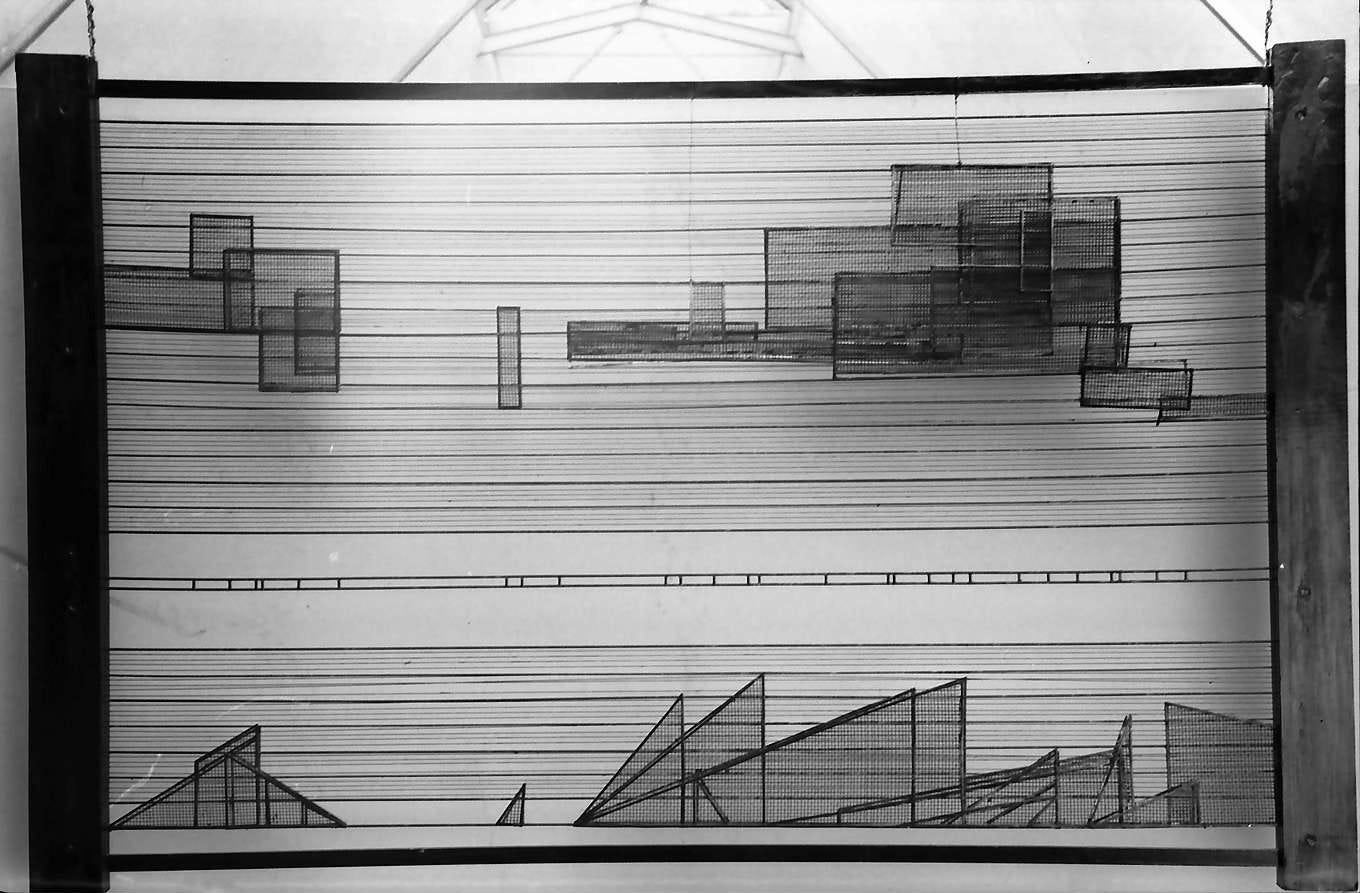

Another example, this one from a bit earlier, and in the realm of electronic music. This is a “sculptural representation” of a score from Karlheinz Stockhausen, of his “Studie II”:2

Here, too, I don’t think it would be any great challenge, even for an untrained listener, to follow along with the score and be able to recognize the recording.

Notation

And this, I think, is a key distinction that serves, for me at least, as the (at times admittedly fuzzy) dividing line between those scores that adopt novel ways of representing musical ideas but still function like a notated score, and those that do not. Because on the other side of this line are scores that don’t allow you to follow along, and therefore don’t function in relation to the sounding event of their performance in the same way.

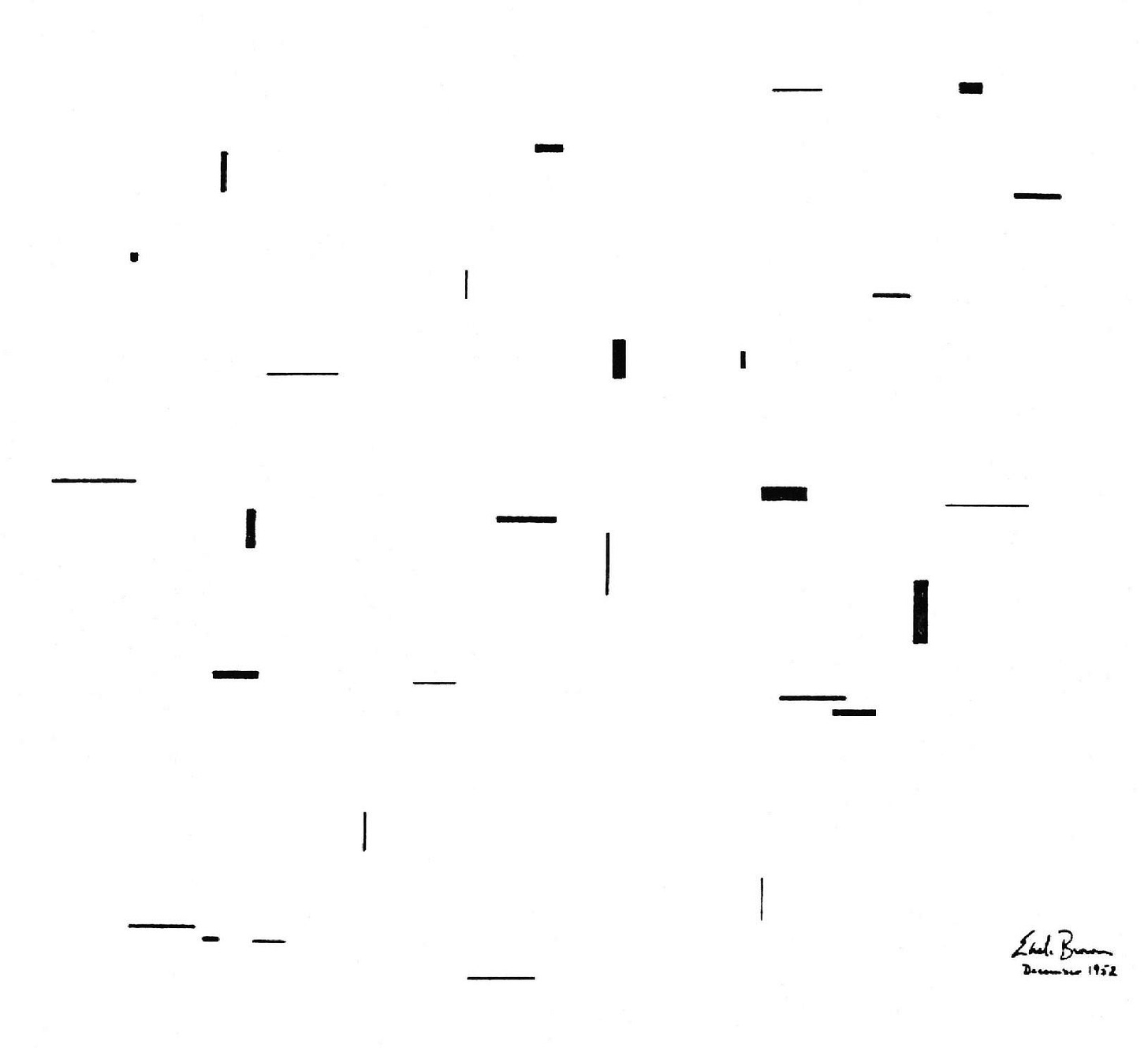

To make this distinction clear, consider probably the most famous graphic score of the early years, Earle Brown’s “December 1952,” which is available at UbuWeb. This is the entirety of the score, from that page:

There’s some really interesting history behind this piece (Brown originally conceived it as a box with the black rectangles mounted on posts, to move them around), but what’s important here is that this score, unlike the previous examples, doesn’t really offer even a trained listener any way to “read” it. If I played a recording of a performance for you, from the audio alone (without some explicitly identifying information) you’d have no way to know you were listening to a recording of this score, and not some other piece by some other composer. The performance notes (also available at that link) don’t provide any help, either: there are some suggestions about how you might choose to interpret the rectangles, but in practice it’s almost completely up to the performer.

And yet I say “almost.” In an interview almost two decades later3 Brown talks about how the performance wouldn’t have been the same if they were playing some other score. Something about this score is exerting a determining influence on the nature of the performance, but our normal understanding of how scores and music notation work aren’t any help.

At this stage, I think it’s helpful to resort to a definition of “notation” put forth by Nelson Goodman in his book “Languages of Art.”4 He’s talking mostly about the visual arts, but he does have a section of musical scores (as they are, somewhat similar to paintings and drawings in his conception, visual objects that refer to some entity external to themselves).

Without getting too deeply into his explanation, a very short version of his definition of “notation” is, I think, a useful one for its functional utility (that is, concerned with how it work rather than what it uses to do so).

Goodman’s Notation

Stated succinctly: it is a notation if it is possible, at least theoretically, when viewing the marks on the page and listening to an unidentified audio recording of a performance, to determine that the latter is a “compliant” performance of the former.5

By that definition, “December 1952” is a score, but it is not a notation. This, then, is the loose thread for me. We recognize it as a score, thus as music, and yet it doesn’t specify in any identifiable way the musical outcome. How, then, does it work as music? If we accept the definition of “music” as an art-form in which æsthetic meaning is communicated through sound, how does that process work for a score that doesn’t specify the sound of the performance? One that will thus sound different in every subsequent performance as well?

Drawing Distinctions

And thus, I’m going to make a point of distinguishing in my writing between those scores that function as “notations” (such as the pieces by Stockhausen and Lachenmann I’ve cited here) and those that do not. The former I’m going to call “musical graphics,” after the title of the exhibition in Donaueschingen in 1959 at which Stockhausen’s score was one of several exhibited. The latter, those scores that don’t communicate meaning in any way I’ve described thus far, I’m going to provisionally call “graphic scores.”

These scores are, I’m going to argue, the loose thread that unravels our understanding of music as an art-form. They are also, I believe, a new and broader way of thinking about how music works; not just for themselves (though they most clearly reveal the difference), but for all music. They are not only the most visually compelling examples of the adventuresome spirit of the postwar avant-garde, but in their existence well outside the margins of our conventional understanding of the art, give us a means to explore new kinds of musical expression that would otherwise be inaccessible.

To close, I want to give an example of what is, for me, one of the most beautiful examples of graphic scores, Roman Haubenstock-Ramati’s “Konstellationen.” This is one sheet out of 24 for the score, each using different combinations of engraving and painting.6 You really should follow that link to the whole collection, but here’s just one example:

It’s not just enough that these scores provide us with a freedom previously unavailable: as I said, I’m not interested in having a license to improvise (not least because of my own limitations as an improviser). These scores are a means to change how we think about music, and change how we think as we perform music.

Like any good art, in the aftermath of the encounter you are no longer who you were before: you see the world differently, perceiving it with other eyes and other ears and another mind, all of which are new and different relative to your past self. You become somebody different from your previous self, unknown and thus unknowable. It is in this transformation that I see the greatest potential for artistic flourishing; and in these artefacts, much beloved by their adherents but largely neglected outside of their respective enclaves, I believe we have one of the greatest attainments of the postwar era.

Utz, Christian. (2016). Time-Space Experience in Works for Solo Cello by Lachenmann, Xenakis and Ferneyhough: a Performance-Sensitive Approach to Morphosyntactic Musical Analysis. Music Analysis. 36. 10.1111/musa.12076.

Landesarchiv Baden-Württemberg, Abteilung Staatsarchiv Freiburg W 134 Nr. 059668 Bild 1. Permalink: https://www.landesarchiv-bw.de/plink/?f=5-433839-1.

“Compliant” is used rather than “correct” in Goodman’s text to avoid, I suspect, problems the latter would introduce if the performer made mistakes or deviations from the specifications of the score.

The entire collection is available here: http://www.ariadne.at/?picture_id=3135&language=en