I’m working on a piece right now that I’m hoping to get performed, and it’s brought up a lot of issues that I haven’t grappled with in years. I took a long break from composing in 2016 to finish my musicology degree, and this is the first new piece I’ve started working on since.

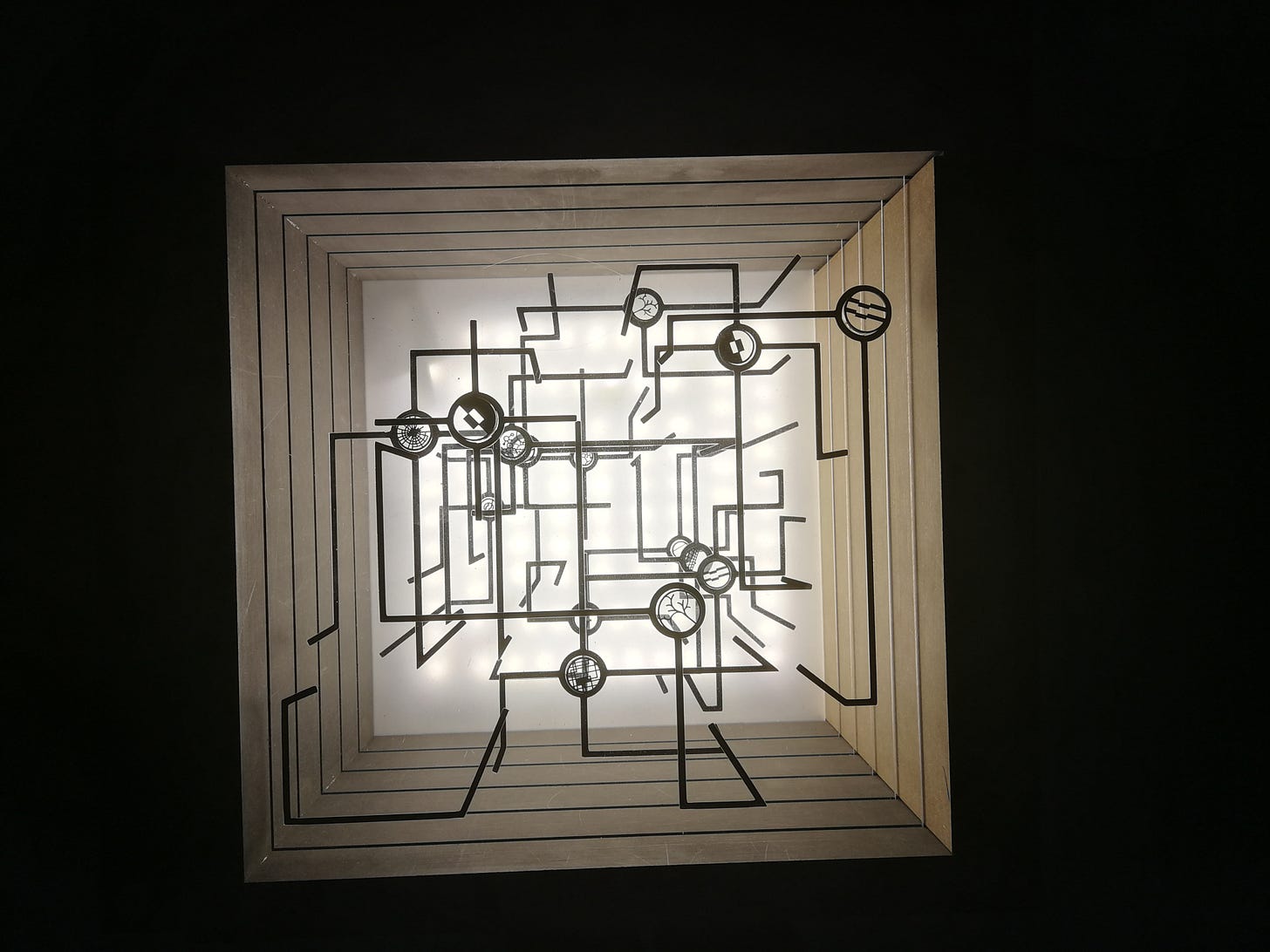

If you’ve looked at some of my other scores—one of them is made up of the illuminated boxes that I used for the header image in a previous article—you’ll note that I’ve generally produced scores that are all black-and-white line-drawing-style scores. This was partly as an homage to the scores of the 1960s (and because I was using the same tools: drafting pens and stencil sets), partly because my original inspiration was logic diagrams.

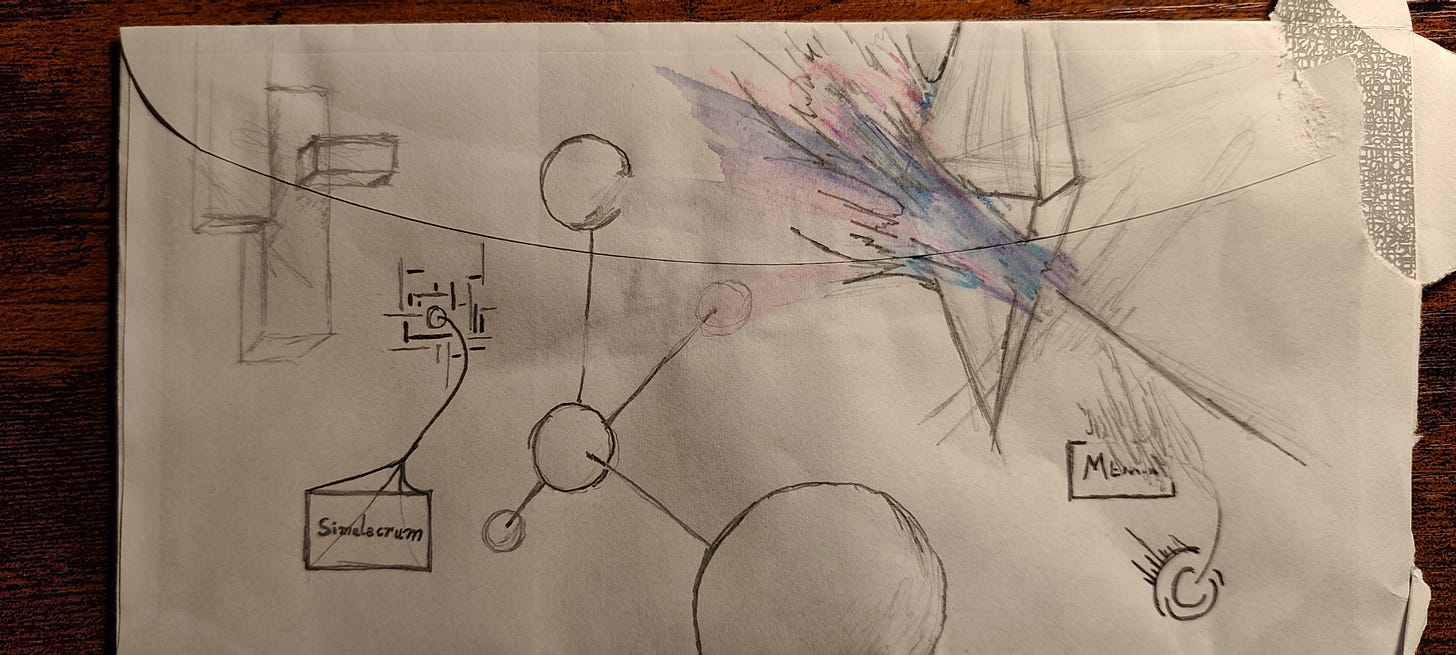

One of the things I wanted to do differently with this score was work in color. That’s going to bring with it another set of technical challenges (I’m going to have to get a bit of a tutorial on how to work with paints, because I think either watercolor or gouache is going to be providing the color), but it’s also going to bring to the fore some questions I’ve been ruminating over regarding how the scores should communicate their ideas.

I don’t want to use color as a directly expressive medium—that is, I don’t want “red” to be interpreted one way, while “blue” is interpreted some other way—but I also don’t want it to be a purely æsthetic tool. I still very strongly believe that the score should perform an essential governing role within the musical exchange, and its visual material consequently needs to be substantive and determinant in relation to the performance.

Put another way, I don’t want this score—which right now I’m conceiving as a set of large sheets of cardstock on which I’ve drawn and painted things—to be approached as if the performers are “improvising in relation to a painting” in the way they might if they were using a conventional piece of visual art. There are plenty of recordings out there of performers “inspired” by Jackson Pollock’s paintings, or Rothko’s, or Kandinsky’s. I have no issue with that, but that’s not what I want to happen here.

Performance Instructions

Maybe I can make this more concrete if I focus on the very specific question of the performance instructions. I’ve been having phone conversations with a number of musicians involved in performing the first generation of graphic scores: those who were working with Erhard Karkoschka or León Schidlowsky from the 60s through the 80s. One of the things almost all of my contacts have said was that having instructions from the composer is essential to having an idea how to approach the score.

So I want to write performance instructions, but I don’t want the instructions to tell the performers what to “do” in the performance. I don’t want to tell them how to interpret any given shape/figure/element of the score, nor give them any narrative instructions about how the piece should unfold, nor tell them what range of sound materials they should use. The musicians I have in mind are all excellent improvisers; they won’t need any guidance from me on finding creative solutions to realizing the score.

But I also don’t want them freely improvising. What I’m particularly interested in pursuing here is a state of mind that I want them to be in when performing, one that should govern how they respond to one another, how they interpret the stimuli of the score and the sounds they hear. So I want to give them explicit instructions, but the instructions have to be governing a level of doing that exists above the level of performing actions. I want to put them in a specific state of mind, so that their interaction with one another and with the score will transpire outside their normal ways of thinking and doing.

The inspiration for my approach to graphic scores was originally based on literary theory, and I came across a whole body of linguistics research (from Lera Boroditsky, an excellent presenter with a TED-Talk you can watch) that demonstrates a strong connection between language and cognition. Habituate people to using language in certain ways, and they become concomitantly habituated to thinking a certain way. I imagine, if you think about it in that way, that this is also how poetry works.

So what I think I’m ending up with here is a set of performance instructions that is going to work like poetry: if you take the text I provide seriously, you end up thinking about things differently, and that affects how you interact with the score. One of the instructions (it’s a set of about 15 short statements so far) reads:

an event may originate in {Undefined}, and may {reinforce/thwart} your actions

What is it supposed to mean when an event relates to your own actions in a way that is both reinforcing and thwarting them simultaneously? What does it mean an event originates not in a definite place that I’m not naming, but a place that is itself indefinite? But more to the point, what kind of language are you using where certain elements mean their own opposite (beyond isolated cases like “inflammable”) or have multiple incompatible meanings? Another example:

your mind comprises fragments/patterns from {Other}

the {image/House} encompasses these superpositions

The first line is a point about our minds that I keep making in my writing: a way of thinking is just a pattern of neural connections, and when you learn a new way of thinking from somebody else, you “copy,” in a sense, that pattern from them. Like an image stored on multiple physical drives in cloud storage, an idea is still one idea, now held by two different physical brains. I hear voices of my former mentors in my head constantly; I’m constantly reminded that my ways of thinking about things are actually ways they thought, now made a part of “my” mind.

The second line makes the point that the score is intended to account for this, and also that the “image” of the score is also a “house,” in the sense borrowed from Mark Z. Danielewski’s “House of Leaves”: that is, a form of labyrinth (which, borrowing from Penelope Reed Doob, takes many physical and metaphorical forms in our shared culture). Danielewski borrows a phrase from Doob to use as the opening of one of the early chapters: a quote from the Æneid, describing Dædalus’ depiction of Crete, including the labyrinth:

hic labor ille domus et inextricabilis error

(“[and] here is the work of that house, of the inextricable wandering”)I certainly don’t expect my performers to chase me down a rabbit-hole of obscure literary references, nor to do a bunch of research on cognitive linguistics. But isn’t that the function of well-crafted poetry? A word, an image, an association— they trigger in us other, unexpected associations, link ideas previously separate, change how we think about things as basic as what a sound your instrument makes means, or how you might respond to sounds made by your fellow musicians. Without realizing it, your mind becomes a different mind. Rather than crushing the language down to fit within whatever mental apparatus you presently have, instead your mind expands to encompass the language, to make sense of what didn’t make sense.

Language

I’m beginning to suspect that this is why all of the composers that interest me also turn out to be gifted poets: the straightforward language we use to give instructions for conventionally notated music (“when you see this symbol, perform this action”) is insufficient for the kind of music they were trying to achieve. The language we have, in the sense of a series of discrete packets of meaning relating one familiar concept to another in stable relationships, simply fails to clarify scores that don’t operate in such a linear manner. John Cage, Yoko Ono, Anestis Logothetis, even Roman Haubenstock-Ramati: all of them have performance instructions that tend toward the uncanny (or, according to their critics, toward pseudo-mysticism).

I sincerely hope that my own performance instructions, tending as they do toward the poetic, aren’t simply dismissed as superficially æsthetic provocations, but taken seriously. They really do mean what they say, and I really do intend, through them, to bring your thinking to a place it wasn’t before. Maybe it’s the case that I’m trying to impose my own peculiar neurodivergence onto you, but it’s my hope that you take the effort in good faith, and that by seeing things a little more like I do we can become, at least in this one small domain of the arts, a little closer together.